Introduction

The Way It Was —

The Fortunes & Misfortunes of the DeWalt Saw

A lot of things had to happen before there could be a Radial Arm Saw of any kind…

Think about this: From the time of Noah and his ark to the heyday of Duncan Phyfe, methods of sawing wood knew little change or improvement. Of course, I have no idea how Noah undertook his unbelievable task—but since the time of the Egyptians, and through century after century thereafter, the story has changed very little: Straight, toothed blades, moving in-and-out or up-and-down, were powered by man until the 15th Century, by water to the 18th Century, and by steam in the 19th Century.

Then, in one fell swoop, all kinds of good (and not so good) things began to happen—all because a quiet little lady, hidden away in a monastic Massachusetts community, had a great idea and did something about it.

Sister Tabitha Babbitt of the Harvard Shakers invented the circular saw blade. The year was 1810. With all due credit and admiration for the good Sister, her incredibly good thinking was well nigh miraculous.

We go all the way back to the Greeks and Archimedes and we find the physical beginnings for our modern helicopters. We go back to Leonardo di Vinci and find he was doing some heavy planning toward today’s airplane. The ancient old-timers were thinking far ahead.

Yet, hard to believe, the great geniuses never seemed to give a second thought to sawing wood. Perhaps they were simply not “in the business” and never felt the need! But, for certain, they had a lot of lowly brothers, through hundreds of years, who were doing some of the finest carving and cabinetry ever seen on the face of the earth.

This reminds me of a song that was popular back in the 1930s—“Everything’s Been Done Before!”

That song’s been bugging me all through my wood-cutting years. My mind always adds, “Yes, and a heckuva lot better!”

Anyway, along comes this little Shaker lady who was in the business—and necessity nudged her sharp mind to make a round saw blade. But I am still in wonderment: What about the untold millions of sawyers through the ages? They all had a need for an improved saw. Perhaps they were so totally engrossed in sawing wood they never had time for a creative thought.

But think of all the engineering geniuses who have come and gone—yet none of them ever conceived that a toothed-wheel was not only a gear but, with sharpened teeth, it just might cut wood.

When Sister Babbitt got that very rare “bee in her bonnet,” she turned the woodworking industry into a much faster moving business. While she isn’t credited with inventing the “saw-table,” as it was called, it was certainly a natural result—and, by 1830, the machine-age had taken over the woodworking industry.

As is always true, you can’t have good without bad.

Some of the finest furniture made, in all of history, was produced in this country of ours—before the Declaration of Independence was signed.

It was exemplary because it was so elegant in design. The rococo styles of the European cabinetmakers were so simplified by the great joiners in our own country—the designs were truly elegant. The names of Goddard, Townsend, Savery, Chapin, Frothingham, etc., were to furniture design and construction what Washington, Jefferson and Franklin were to politics.

The fundamental approach to religion by the Puritans, the influence of the Quakers, and the damnable desire to get this new country going, produced a quality of furniture that would never be seen again.

I’m certain Sister Babbitt was the last person who’d ever want to put an end to such a great era—but she most definitely helped. The days of the great cabinetmakers were over! All that was left was Mr. Phyfe (with all due respect), who finally succumbed to the design whims of his wealthy customers—and the profitable whine of mass production began.

Design was drastically affected in favor of all kinds of new machines with round blades and round cutters.

It reached its lowest ebb in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with machines chewing up forests of maple, to be stained a gauche, orange color—and screw-heads, covered with protruding plugs, became a most desired feature. True enough, all those dreary rows of houses, in all those mill-towns across America, needed functional furniture they could afford. But our Industrial Revolution was the death of good taste in furniture design.

DESIGN is EVERYTHING!

Without good design, the greatest craftsmanship is wasted.

Not all great museum pieces are of the best craftsmanship. It was design that made them a treasure.

Gone was the Queen Anne panel with its squared, inside-corners at the arch—a feat that can never be accomplished with a round cutter.

Gone was the master-carver’s touch on the cabriole leg and the ball-and-claw foot. Impossible for a machine, such gentle designs were discarded at the altar of “production.”

Thus, Sister Babbitt, seeking to aid in the making of their beautifully simple Shaker furniture, actually started a decline in the quality of our furniture that continues to the present day.

Another of the “culprits,” as were all machines, would be the Radial Saw. (Strange for me to say that, but it’s true!) It would be more than an-other century before it could even be invented. Unlike any other machine you can name, it could never be run by belts or primitive power.

Mr. Edison had to create a new kind of energy—and that power also had to be distributed. Not until a President, by the name of Roosevelt, came up with Rural Electrification, was electricity taken beyond the industrial cities and into the hinterland. Meanwhile, old fixed-arbor table-saws, with all kinds of tilting tables, were being powered by whatever was available—water or steam, transmitted by wide, slapping, flapping leather belts. Though big, inefficient, electric motors later became the new power source, the wide leather belts kept right on slapping and flapping away.

At that moment, when the combination of electricity and the new round saw blade made the radial-concept a possibility—it still could not happen. The time was not yet quite right. The market wasn’t ready. The need wasn’t great enough.

But it wouldn’t take long!

America had moved into the 20th Century—into and through the first World War. Electricity was flowing through wires strung into the growing industrial centers of America—reaching into the very areas where post-war housing requirements were pressing for answers.

World War I veterans had come home from “over there”—and they needed houses!

The construction industry was badly in need of faster methods for cutting framing members. The cabinet industry needed “idiot-proof” methods for precise cutting—to get professional results from less costly “hired help.” New materials were being developed—requiring new techniques for “special cutting.”

What was needed was a new kind of 20th-Century saw—and a fellow in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, was ready!

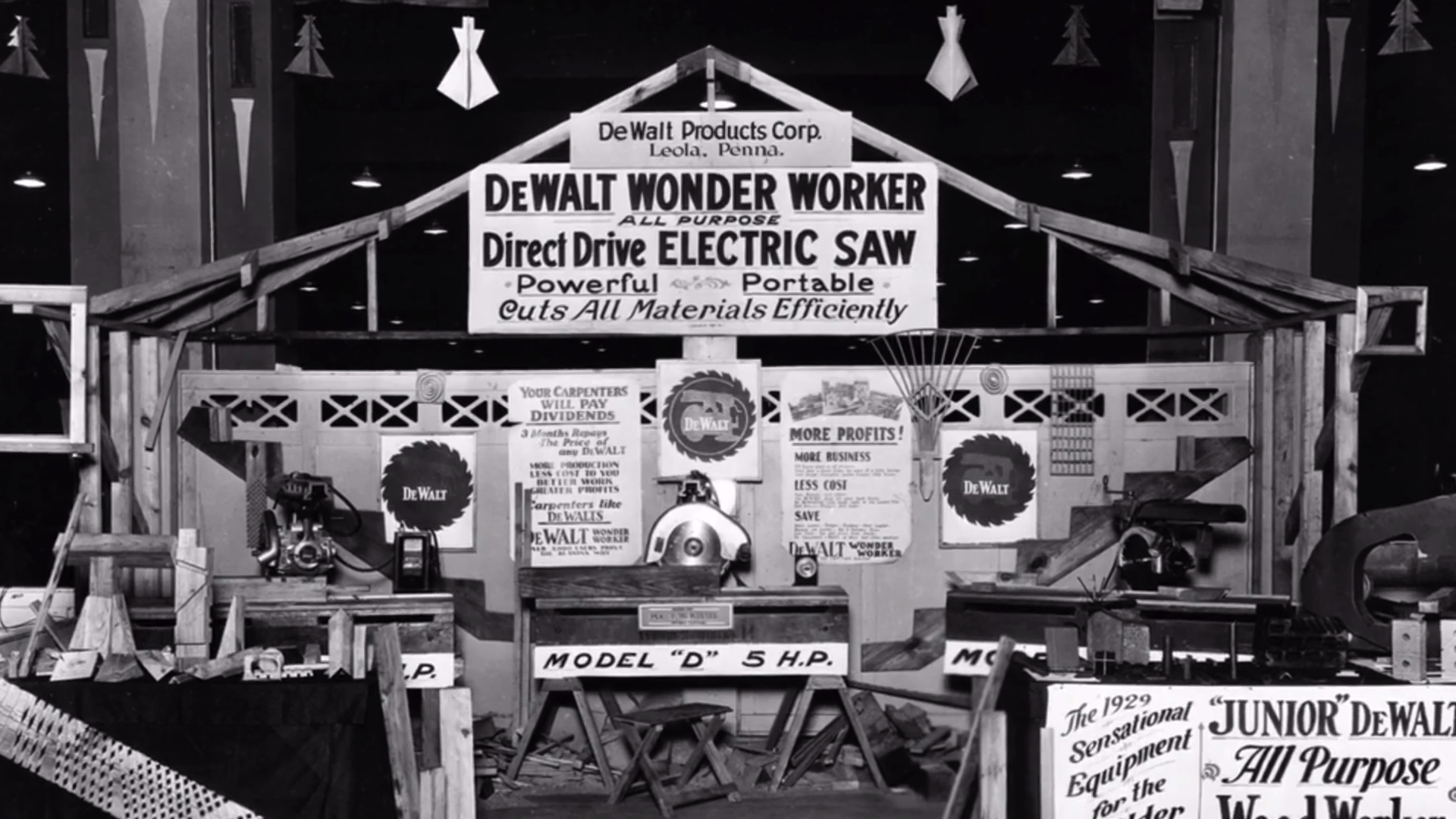

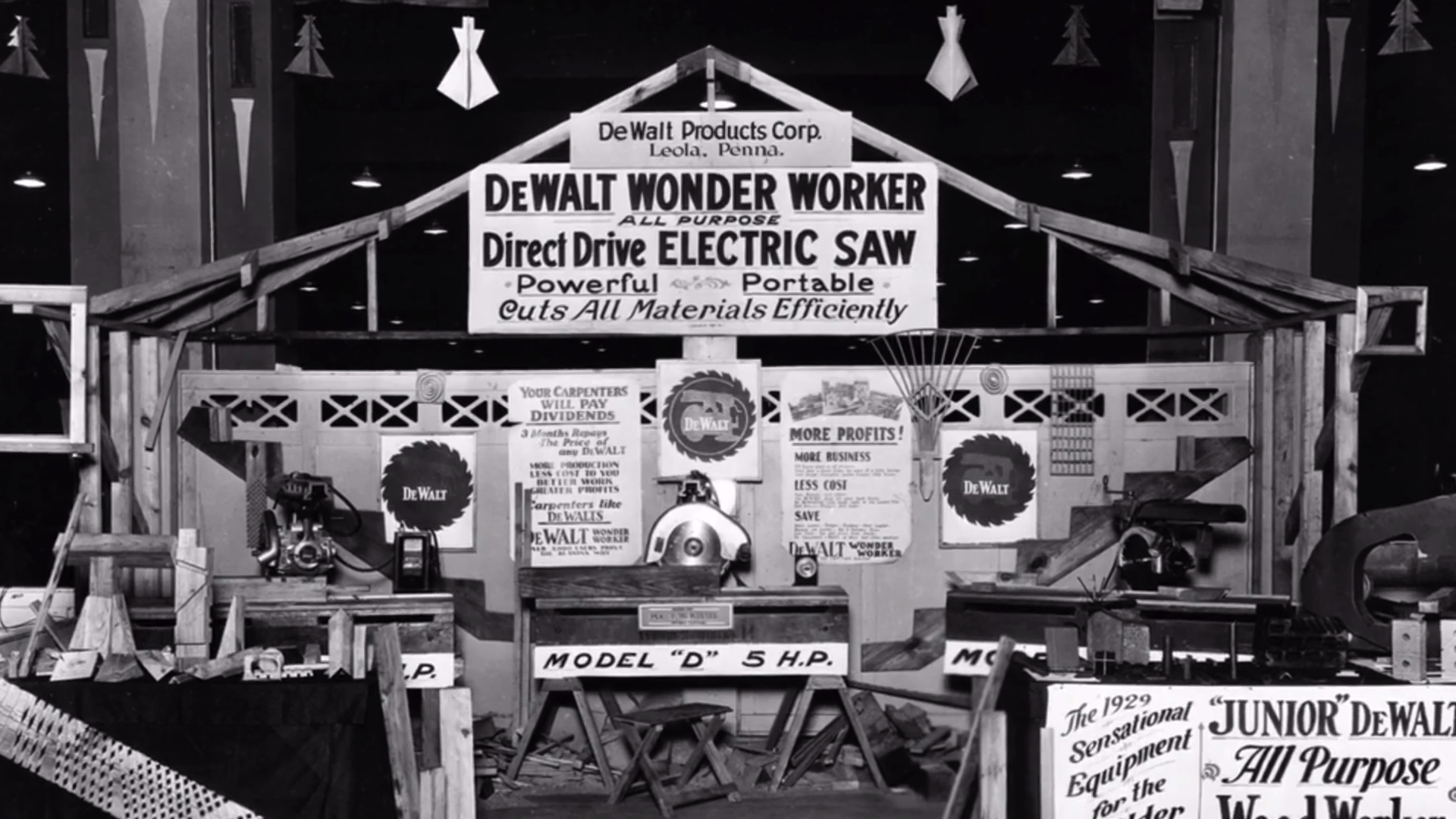

An industrial-arts teacher, Raymond DeWalt was already producing radial-arm machines in a three-car garage.

Simple, sturdy, contrivances of utilitarian design with five-horse-power motors.

They would cross-cut and make a flat miter—but the motor did not tilt for bevel cuts or compound miters. The only bearings were in the motor. The motor traveled on a length of heavy, greased, steel bar-stock. It sat on a wooden base. It’s name:

“The DeWalt Wonder Woodworker”

Whether Raymond knew it or not, the doors of the Construction Industry were wide open—and he walked through. Better yet, he took a train! He left his manufacturing in capable hands and headed out for Florida where there was a surging land boom.

As the story goes, he never got there! Instead, he met some of the “right people” in the dining car and sold a train-car-load of his “Wonder Woodworkers” without ever setting foot in Florida.

Thus, the beginning of a great story of innovation and entrepreneurship.

The building of Levittown, NY. A mile of DeWalts (farther than you can see), lumber, roller tables and men.

From the 1920s, to the present day, wherever builders could set up for gang-cutting operations on-site or pre-cutting operations off-site, the DeWalt has been an amazing performer.

My introduction to this sort of thing was in 1948. Mr. DeWalt was still around the plant and his brother was still “keeping the books.”

He had just sold his company to American Machine & Foundry—and I was in their New York advertising agency, the writer on the AMF account (and a woodworker in the basement of my home in South Orange, NJ). Somebody in the agency suggested I go to Levittown, on Long Island, for a “little education” on the DeWalt.

What I saw was probably the single most extensive use of radial-saws ever conceived.

I saw a row of huge, 7-1/2 hp DeWalts (Model GEV)—18 of them, in gangs of six—standing in a single straight row, ONE (1) MILE long—separated by long roller-tables and surrounded by big stacks of lumber as far as I could see—standing there like huge animals waiting to be fed.

Material would be loaded on the front-end of the production line. A dozen 2x8s, 2x6s, or 2x4s on edge, strapped together like one solid timber, moved along a conveyor from one machine to the next in each gang—all sitting in a straight line.

Batches of ends would be squared in one sweep of a screaming 20” blade. The next DeWalt would cut them all to length. Then a dozen rafters, on edge, would be cut with beveled-ends on another DeWalt—then cut to length with a duplicate bevel on another DeWalt—then notched, in one full sweep, with an angled 12”-diameter shaper-head on another.

At Levittown, whatever would be required for studs, rafters, and joists—a complete house of framing members—were cut every 23 minutes.

I need to change the subject for a minute.You’ll be seeing photos, throughout the early pages of this book. Their quality won’t be the best. The reason is simple: The originals burned up in a fire at the DeWalt plant. I probably have the only copies that exist—and you’re looking at a copy of a copy! Plus, they’re over 40 (maybe 50) years old!You’ll also see punch marks from the 3-ring binder that’s kept them all these years. Sorry about that — but it’s better than no pictures.

1500 Houses in 65 Days!

It was the only way for War Veterans to own a good home for under $7,000!

During World War II, the Army Engineers had a need which resulted in one of the most unusual requests ever made to a machine manufacturer.

The Army needed the largest DeWalts possible—and weighing as little as possible. Magnesium was the answer—and any machinist knows the difficulties and hazards of working magnesium. Worst of all, it is extremely combustible. Chips of magnesium will start a fire with no seeming provocation.

What they wanted were DeWalts, each with its own generator, mounted on 2-wheel trailers—light enough for two men to lift easily. Except for the two rubber tires and the windings in the DeWalt motor and the generator, they would be made entirely of magnesium. They were to be parachuted into Pacific battle zones where they could immediately go to work cutting bridge-timbers.

A few of those machines must still exist somewhere. Being magnesium, they would never rust—even if they’re still sitting in a jungle somewhere. I saw one advertised in Philadelphia some years ago—and I’ve wished ever since I’d bought it.

War time or peace-time, the DeWalt Saw found a ready and continued acceptance by the Construction Industry.

As for “Heavy Industry,” it was a different story—much slower in acceptance. There was a reticence—which can always be expected in that market—especially for something totally new.

The attitude of “heavy” industry is to let small industry barge in and make all the mistakes—to prove the need. They hold back till “the bugs are out”—and continue with established methods as long as possible.

The truth is—the larger the company, the more reticence! It’s full of committees—individuals who are expected to make decisions, individuals who can’t make decisions, and individuals who won’t make decisions. Such groups of people tend to cancel each other out in the planning process.

Eventually, however, one of the group will finally surface as the decision-maker—and he too often also decides against your totally new idea or product!

Faced with ever-increasing production requirements, however, the large companies eventually began to learn that men of little experience could produce accurate results with this new kind of saw—starting with their first days on the payroll! And, as the die-hards lost their “say,” the DeWalt moved in—and stayed!

Small companies and cabinet-shops had their own kinds of “stand-offish-ness.” The owner would often be more entrepreneur than woodworker, a lover of new ideas, and could make a quick decision to his profit-advantage and his spirit of adventure. However, there always seemed to be that well-entrenched, old woodworker—running the shop with an iron hand—known for the fingers he’d lost to a saw-table.

He wanted nothing to do with that new “Radical Saw”!

Machines with an inhuman control are always resented by humans who resist change—especially if they’ve lost their desire to keep pace—and, most especially, if the change has something to do with their job status or future. How strong those individuals are in the decision-making process has every thing to do with product acceptance.

In the case of the “radical-saw,” it faced an industry where the table-saw had, at least, a 100-year head-start. Fifth-generation woodworkers, boasting fists-full of short fingers, hooted at the DeWalt. The belt-makers (a very big industry) also hated it with a passion. It was the only machine that could never be run by a belt.

Even the prospect of making a half-dozen good-looking cuts with accuracy (instead of one cut that looked like they’d chewed it off with their teeth)—was revolting, to say the least. While DeWalt salesmen “cooled their heels” in big-company reception rooms—it became a matter of slow, but anticipated, change.

In those smaller shops, the old-timers also continued to cling tenaciously to the “I-can-do-anything-with-my-table-saw” bromide and, because they had much to say about machine purchases, we could only wish them well—and depart.

They resisted any idea of the “two-saw” shop with real defiance. Even if the boss might go ahead and purchase a radial-arm, he quickly found he’d wasted his money.

The machine was treated like it had the plague—crouching against a far wall, always in poor alignment (worth-less even for “cut-off”!), with its table usually covered with junk—and kept inaccessible to the younger fellows who might like to “try” it.

That term, “cut-off,” became a virtual whispering campaign against the DeWalt through the years—even continuing up to the present day. It conjured up visions of the old pendulum-type, belt-driven swing-saw which had possibilities of mayhem second only to the guillotine! Every saw-mill had one!

In the early days, the whispering was effective. Today, however, such reference simply reflects on the man who’s doing the whispering. (But the old codger still mutters to himself!)

There’s another industry that’s getting a lot of deserved criticism these days—and I intend to heap on a little more:

Our industrial arts schools!

It’s a fact, the radial-saw was an American invention which never caught on in Europe as it did at home.

This would be of little concern except that a great number of “Old World” woodworkers came to this country, bringing with them the seeming aura of Old-World craftsmanship, and many of them became teachers in our schools at all levels. This has resulted in several generations of Industrial Arts teachers requisitioning table saws, producing talent which is supposed to go out into industry—to face what? A table-saw, of course.

And a DeWalt, most certainly!

The school industry has continued to degenerate toward its present condition of near worthlessness. Their shops are filled with the most expensive machinery they can order, foisted on them by favored machinery houses, and paid for by the local taxpayers.

The Old-World craftsmanship, if it ever was, is no more. The new generation of teachers has never learned the pure techniques of hand-joinery—the foundation for all good woodworking.

As for the machines, they can hardly find the ON/OFF switch.

No longer is fine cabinet-making even a subject in the school curriculum. Instead, the students drive nails into studs for a house they’ll raffle off, build a boat for somebody’s summer vacation—and stand in line for group therapy sessions of all kinds.

Mr. Sawdust (1952) demonstrating the best DeWalt model ever produced (GWI)

– at National Industrial Arts Convention, Atlantic City, NJ

My desk, at the agency in 1948, was covered with DeWalt literature—all Industrial. (For a fellow who went home to a Shopsmith every night, it was frightening!)

But I’ll let you see those big DeWalts for yourself.

For the serious woodworker, this is exciting history—and also a very important reference if you’re on the trail of a used machine of this vintage.

Many of my readers own these same machines—and, after 40 to 60 years, I’m certain there are many, many of these DeWalts still in operation—and, I am certain, they’re also available on the “used” market.

On page 15 you’ll see the little DeWalt that not only changed my life (totally!)—but the lives of thousands of other people.

It can also change yours!

This was the Model GE—work-horse of the industry A “Long Arm” was available that gave a 31” cross-cut and a 44” rip. A beautiful machine!

In my opinion, the Model GA is almost too big for the cabinet shop. However, with a “Medium Arm”, it gave a 24” cross-cut! Perfect for wide plywood cuts.

This Model R2 was always my favorite of the Industrial DeWalts—but it had a Receding Arm and would not sit back against a wall. Had a greater rip capacity than GA.

The Two-Post GO would cut up to 12 feet, would rip at any point. Motor would tilt.

The GW started out as a 10” size. Later, they put a 12”-guard on it with no increase in power. When this picture was taken, the GWI (single phase) sold for $349.

DeWalt Timber Cutter (TC-12) was a real monster. Up to 36” blade. Johns-Mansville had a dozen that cut miters on large transite tubing.

The MB—smallest DeWalt. The machine that captured the hearts of Do-It-Yourself America—because it just happened to be the greatest saw in the world. And still is!

My first son, Marc, at the age of three

— starting his career! He’s 47 at this writing. Now he designs and builds interiors for fine residences and banks in New York City.