Timeless Advice

The Master Plan

“There is a Master Plan for each of us. Because we do not comprehend this Plan without living through it, we must each devise our own “working drawing”, our tentative goals — and detailed drawings for our momentary, precise actions. Just as the craftsman is never completely certain of the accuracy of his drawings, he must proceed with care — proving and disproving, compensating, adjusting, blending together — so many things that cannot be drawn into plans.”

This is not the first time I’ve stumbled across truly timeless, much-needed encouragement and advice that I’d somehow missed while scanning and archiving these newsletters. It’s short and to the point, as most worthwhile wisdom often comes – and written in a way that can only come from someone who knows what it is to make grand plans and craft masterpieces – and also to falter, to fail, and to rise again – and consider what to build next.

What follows is an excerpt from the September 1979 issue of Wallace Kunkel’s Bench Talk newsletter – which was his unique way to share the news and happenings at the original Mr. Sawdust School.

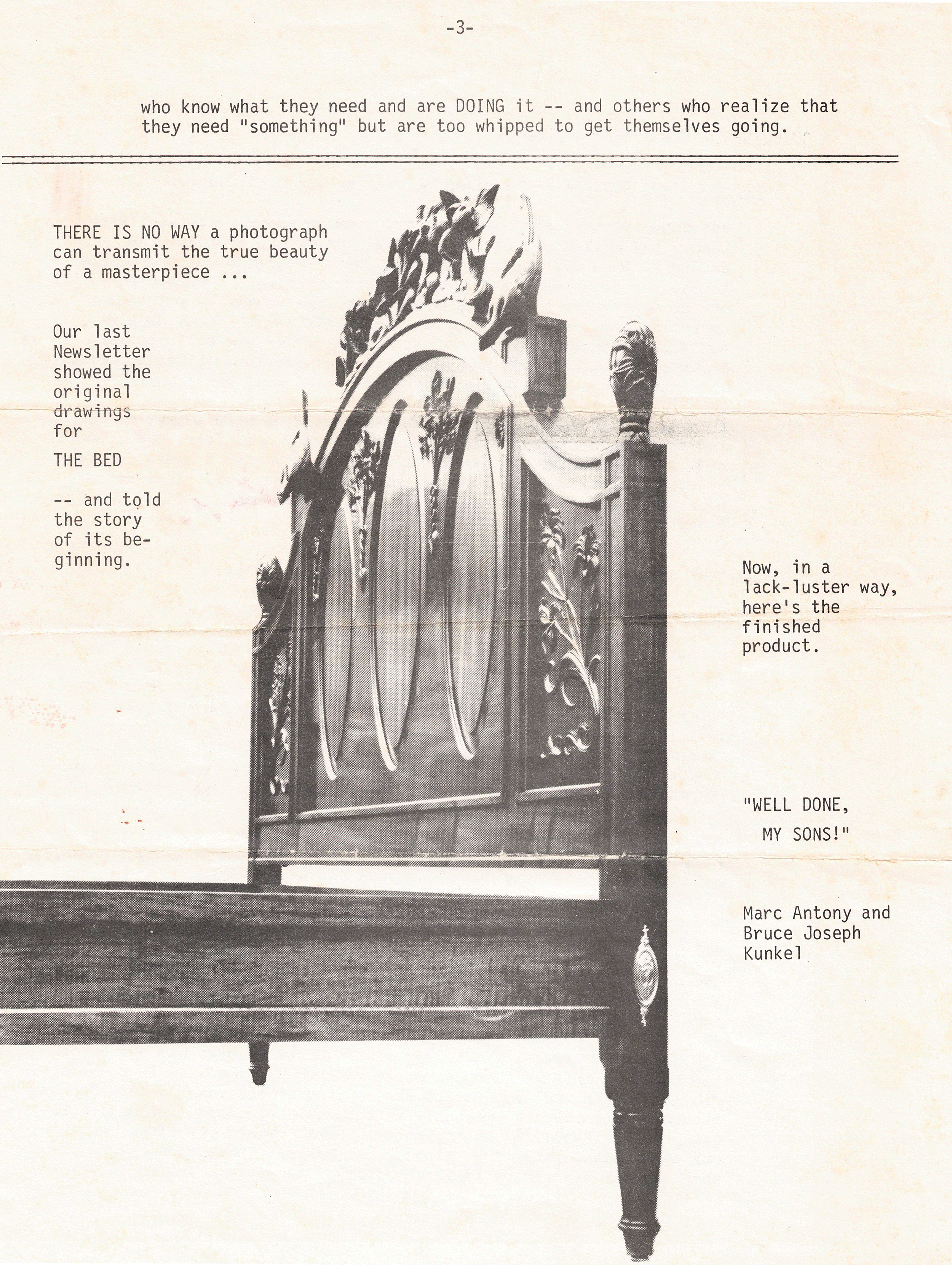

At the time of this newsletter in 1979 (and the one prior), Wally was enjoying a father’s pride, sharing a remarkable project undertaken by his sons Bruce & Marc Kunkel – the Lily bed – a masterpiece of furniture design and construction. In the May 1979 newsletter, he includes a brief detailing of the project, complete with fine drawings. I’ve included one below. In the next newsletter, he shares photos of the completed work, and a sentence every son can appreciate hearing from his father – “Well done, my sons!”. I have to imagine he had this level of craftsmanship – and whatever had to happen for these men to take such a project from “drawings” to “done” – in mind when he wrote his words below.

The photo atop the page is another favorite of mine – Wallace standing over this project, at some point along the way. This moment, from this photo, came to mind as I was reading his words. One phrase struck and stayed with me – “the Master Plan” – so it seems a fitting title to give this bit of writing. Highlights and emphasis throughout are my own.

— David

What did 15 people really learn this summer of 1979?

It is not really and finally important that we began with a pile of mahogany boards and created a pair of masterpieces — copies of a Block Front Desk that stands in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum, NYC. My use of the word "masterpiece" is not too strong. One of these desks will be on display at the school during the month of October — and you can decide the quality for yourself.

The class lasted for 33 sessions (three evenings a week) — and our subject at this moment is: WHAT WAS REALLY LEARNED?

The pursuit of building an exemplary piece of furniture is not only a long, arduous test of patience and skill — but it forces a close comparison to the total life of a human being.

To a young man of integrity and impatience, the lessons to be learned can come as a shock — as will much of life!

To a man of 50, more or less, he finds a certain solace and verification in the lessons he has lived through — and can now qualify their importance.

Only till a life of well-intentioned and morally-guided human endeavors is completed — only then can it be looked at and appreciated. A fine piece of handmade furniture has an identical parallel:

The most professional craftsman will never begin without "working drawings"— and will remain alert to possible errors and the slight modifications which must be anticipated. He, as well as his drawings, is always subject to human error — sometimes irreparable, sometimes of little consequence but forever-after a reminder of his ineptness. So it is with every man's life.

There is a Master Plan for each of us. Because we do not comprehend this Plan without living through it, we must each devise our own "working drawing”, our tentative goals — and detailed drawings for our momentary, precise actions. Just as the craftsman is never completely certain of the accuracy of his drawings, he must proceed with care — proving and disproving, compensating, adjusting, blending together — so many things that cannot be drawn into plans.

So it is with life.

There is no perfect craftsman. No perfect human being. Every great man has erred, has strayed, has something of which he does not speak. Yet the end result can certainly be that he is (or was) a GREAT man.

The finest of museum furniture, elegant and priceless, has flaws. Human frailty and inconsistency, from centuries ago, will show through somewhere. But — in the final masterpiece, the total result (the total life!), we see only the complete, creative, living effort. Design, and proportion, and patience — with good taste and persistence — these are actually the values that are recognized and admired in the end.

The little "dings", the slip of the chisel, the distortion of a moulding, the slight misfit of a dovetail — perhaps serious for the moment — but nothing more than the expected imperfection of man. (In his everyday life, these are sins for which he can be forgiven and will, hopefully, try not to repeat.) By moving ahead with a damnable desire to improve, the craftsman will work through all the necessary procedures required for the finished product (scraping and filling and oiling and waxing and rubbing, etc.) The small flaws lose their importance — many disappear completely — and some even become "beauty marks" — evidence that a human was doing his best — except for that inevitable moment of fallibility. At the least, he was DOING.

Oh, we learned many things. We had produced two lovely, very valuable, MATERIAL objects. But, more than that, we had known a personal camaraderie. And arrived at an unusual, comfortable closeness. What had started as 15 highly-diverse individuals, very aware of the other person's quirks and experience or inexperience, became a most unusual group — welded together by a quiet compassion and understanding, a common purpose — and a new look at life.

Tell me: In what other way can a Masterpiece result — be it Man or Desk?

Grandad Ezra used to say, "Woodworking is a most admirable profession. If you're any good at it, you spend as much time admirin' what you did ‘as you took to do it."

God bless you ALL.

Wallace Kunkel

Mr. Sawdust