Chapter One

The Great Do-It-Yourself Era —

This was the beginning of the most exciting time of my life – the great Do-It-Yourself era.

Veterans had returned from the War and had to do it themselves. (They also wanted to!) They came to the Home Shows across America—literally, in droves.

Shopsmith was the “big” name. It was, and is, basically a lathe turned into a half-dozen other machines. Their original factory demonstrator was a fellow by the name of “Red.” I don’t remember his last name—but he was a master of woodturning. The wood seemed to melt under his chisel into fantastic shapes. He was also a great showman!

My goal, like many others, was to own a Shopsmith. I wanted one so badly I could taste it! At that time, I worked on Madison Avenue and 40th Street, NYC.

Directly across the street was a Patterson Brothers tool store—and I went out of my mind every noon hour. They sold, and they demonstrated, my Shopsmith!

My wife and I were having the first of our six sons and one daughter. Marc, my oldest, had outgrown his crib and needed a bed. We liked “Early American”—so my wife, Jean, told me I should buy one for him.

I did. I went to Altman’s and paid $150 for it (a lot of money in the 1940s!) When it was delivered, Jean phoned me at the office and said, “This bed’s not worth the money. How much is that Shopsmith?”

“$350,” I answered, hopefully. And she said, “Buy it!”

Nothing in the world could have kept me at my typewriter that day. I went straight across Madison Avenue and walked into a totally new kind of existence—at the cost of almost a month’s pay! (Not quite, but it sure hurt the budget!)

I then found out there was such a thing as a lumberyard that sold only hardwoods. I’d never heard of such a thing! It was in the bowels of Newark—but I would have found it if it had been in Timbuktu. I told them I wanted Maple, “Three inches thick.” They said, “You mean, 12-quarter.” (Wow, I was beginning to learn the language already!)

What I didn’t know was they would have dressed it into nice 12/4-square turning-stock for a little more money. Instead, I went back to my Shopsmith and labored the big planks of rough Maple into the turning stock I needed. (What a job! I had a lot to learn.)

The end result was well-nigh miraculous. I had bought enough for five turned bed-posts because I knew I would ruin at least one. But I didn’t. SO, I only needed three more for Bruce’s bed, my #2 son! (That meant another trip to Newark.)

My father, a farmer in Missouri, came for a visit later. I asked him, “How do you like the bed?”

He liked it.

“Where did you find that nice Birch?” he asked.

“Birch!? It’s Maple!”

“Nope. It ain’t Maple. See that little freckle in the end-grain? That’s Birch.”

“Anyway,” I said. “It’s 12/4!”

This was the beginning of an addiction that resulted in my building an “Early American” house, ten rooms of furniture, and searching for a way to get out of the advertising business and into the world of woodworking—as fast as possible.

When AMF bought DeWalt, I had my answer.

I convinced Morehead Patterson, CEO of AMF, DeWalt could “take over” this exciting new Home Industry. I did a marketing study in Northern New Jersey and came back all excited. By this time, he had made Sam Auchincloss the President of their DeWalt Division. (One of the greatest gentlemen I’ve ever known. Jackie Kennedy’s uncle, I think.)

I said, “Sam, we can sell $1,000,000 of DeWalts, per year, in the north ten counties of New Jersey alone!”

After he hired Condé Hamlin for National Sales Manager, they both showed up in New York, took me to Rockefeller Center for a nice lunch, and said, “DO IT!”

While Condé put together a sales force of 30 District Managers across America, I did the original marketing and sales promotion.

You’ll soon see that we turned that little DeWalt into 12 “machines.” (Nine of them were a real stretch of the imagination!)

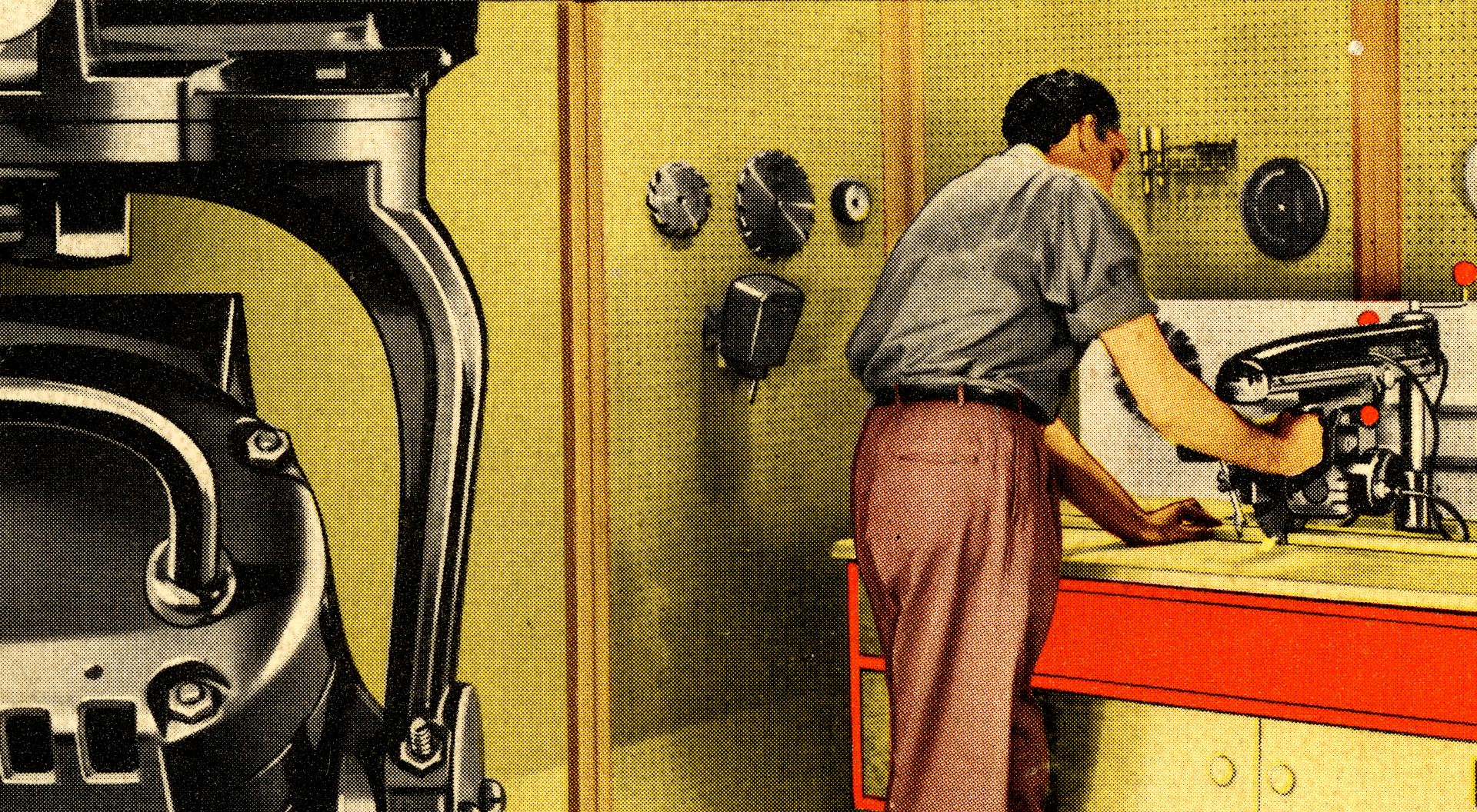

What I’m about to show you is the cover of the only existing copy of our first literature for the little DeWalt.

We gave it a new name — “DeWalt Power Shop” — and described its “3-Dimensional, Self-Measuring Principle” like it had never been described before.

There! You’ve just been introduced to the most successful machine that ever hit the Home Market.

It had polished castings. It had a cadmium-plated saw guard and bright red control handles. And, some of you will remember—it performed!

After setting-up the national program, I took Northern NJ for my District. With 125 dealers, all trained and demonstrating (most of them with their own DeWalt Department), we made my original prediction come true.

What a great bunch of dealers! Big and little hardware stores, big and little lumberyards, Mom-and-Pop operations that sold only DeWalts, and old-line machinery houses who actually resented “these home-owners” coming into their showrooms (till they found out there was money to be made!).

Today, one of them is among the top houses in the country—a father and son, in those days—and I remember when they were selling DeWalts out of the back-end of a pick-up and keeping their inventory of machinery in their home garage.

My District never sold less than $1,000,000 worth, per year, for the next ten years. In the Power Shop line, we had two models, the MB with 3/4 hp—and the GW with 1-1/2 hp. They sold for $229 and $349, respectively.

My dealers were buying them 50 at a time. In fact, with myself and two assistants, demonstrating in the parking lot of a well-known lumber company, we sold a trailer-truck-load over a weekend. 219 DeWalts!

I had a dealer in Bayonne, a hard-ware store, who had no warehouse. He moved all his “islands” back and stacked his 50 DeWalt boxes in layers around in a big circle—like an amphitheater. The crowd used them for “bleachers.” By the time we got finished “cutting wood” for a few days, he didn’t need a warehouse.

A fellow, named Tom Berry, was the District Manager in New York. We were at each other’s throats all the time. Good friends, but ... ! He had a very smart dealer, Howard Silken, who set up a permanent, full-time, live demonstration in the Bus Terminal in Manhattan.

Most of the NJ commuters went through that station—whether by bus or subway. The more we “cut wood” in NJ—the more machines they’d sell in NY. Up to then, I thought the whole world was mine!

(It was—except for Manhattan!)

Northern New Jersey bought over 3,000 DeWalts each year for ten years. (NY sold a like amount—and California always outsold everybody!) Chances are, most of those machines exist today!

You’re reading this book, for one of two good reasons: You either own an early DeWalt—or you wish you did!

It’s my honest opinion that within a very few miles of you, there’s a beautiful old DeWalt just waiting for you to own it. All you have to do is find it.

A little ad, in a little newspaper, can do the trick. Don’t let it sound like you’re willing to pay just any amount of money. “Looking for old DeWalt Power Shop. The older the better. Any condition. Must have solid cast arm and the motor must run.”

With this book, you’ll be able to put it in “like new” condition. In fact, better than new!

So, this is the story that Do-It-Yourself America learned to love…

I well remember that I “worked” the very first Home Show that was ever held in the 34th Street Armory in New York City. That was in 1948. It was also the very first Home Show to be televised—which made it a very big event. TV was in its real infancy, everything was “live” and a very popular lady by the name of Mary Margaret McBride came into the armory with a huge camera and lots of long, fat wires and decided I was to be her subject.

While she was getting ready, I met an even bigger personality by the name of Norman Brokenshire. He was the most famous of the radio commentators at the time (the Cronkite of his day)—and also quite a woodworker at his home in Ronkonkoma, Long Island. Alongside him was a young comedian with a “butch” haircut, a newcomer to television—and his name was George Gobel. If you’re old enough, you’ll remember “Lonesome George” for his—“Well, I’ll be a dirty bird!”

While Mary Margaret was focusing on me and my DeWalt, she also decided that I would “make something in 60 seconds.” I guess I looked a little lost because Brokenshire started coming up with suggestions—the best of which was, “Make a box!” After a little head-scratching, I agreed with him.

So, with the big camera whirring, Mary Margaret commentating, and “Broke” and Gobel telling me how many seconds I had left, I made a half-dozen saw cuts, changed to a dado-head and made a half-dozen more cuts, and started picking up the pieces with “Five seconds to go!”

The whole thing snapped together at “Two!” and I held up the box to a cheering, counting crowd at “Zero!”

Gobel turned to Brokenshire and said, “We call him Mr. Sawdust! Yessiree, that’s what we call this fella!”

And that’s been my name ever since.

Gobel turned to Brokenshire and said, “We call him Mr. Sawdust! Yessiree, that’s what we call this fella!” — and that’s been my name ever since.

The demise of DeWalt began about 1958.

We acquired a Sales Manager who was a former Washington lobbyist and thoroughly greedy. If I tell you he raised worms in his basement, you’ll understand he also had other problems. The combination resulted in his allowing Sears to sell DeWalts.

It took 4,300 DeWalts to fill the “pipeline” into the Sears stores in my area alone—and I never made a call on one of them. I resigned. My 125 dealers quit all in the same morning. I took my wife, and a nice fat commission check—and the next boat to Bermuda.

Black & Decker bought DeWalt from AMF around 1960. Typical of most industry in those days (the tool industry, in particular), salesmanship succumbed to mere order-taking. Demonstration and customer-training was no more. The great Home Shows were a thing of the past because there were no exhibitors.

With competition from a new radial-saw line at Sears, B&D evidently began to lose position. They both put 12” blades on machines that were powered for 10” blades. They both talked “developed horsepower” and the customer thought he was getting more for his money. When Sears moved their elevating handle to the front of the arm, B&D bowed to them. They threw away their solid cast arm (on the smallest DeWalt) and introduced all kinds of design complications in an effort to be competitive.

It was the era of the “Detroit Syndrome” (Give it fins and it will fly!). Features without function. I sincerely believe—if they’d left the smallest DeWalt exactly like it was during it’s heyday, they’d have whipped all comers. (A little sales-effort would have helped, too!)

The end came in November, 1990. The DeWalt was “discontinued” by Black & Decker. (I find myself resenting all those B&D blenders and can-openers and flashlights.)

While I don’t know the whole story, I’m well aware of the years they simply neglected America’s “dream” machine.

For the sincere wood-worker, however, this just may be the best thing that’s ever happened:

There are thousands of DeWalts, hidden away in unused shops and basements, that are probably as good today as when they were manufactured. When you find one, make sure it has a solid cast arm and the elevating handle is on the back of the arm—not on the front. Make certain it has at least 3/4 hp (9 amps)—or, better yet, the motor is labeled “12 amps” (1 hp). Or better yet, 1-1/2 hp (17 amps). For best success, on those sizes of machines, use an 8” blade for most of your work—even though it will take a 10” or 12” blade. If you find a larger DeWalt—(but not larger than a 14” blade with 5 hp—too big for a small shop)—buy it! One thing more, it will either have a single-phase or a 3-phase motor. Three-phase DeWalts are great, if you have 3-phase power in your shop. Last thing: Plug it in. See if the motor runs. If it does not (but it hums) it may be a simple problem—like a new condenser or relay—but if the winding is burned out (very rare), forget it!

For a nice finale to this section, I would like to paint a big, beautiful picture for you—with thousands of happy woodworkers, busy as beavers, turning out great works of art to the astonishment of customers and wives.

I can’t do that.

I will remind you that great numbers of people succumbed to the radial-arm concept, long after DeWalt was on the decline—but I seriously doubt if even a small fraction of those well-intentioned owners ever got close to the satisfaction they sought.

Let me explain: There is a world of difference between the radial-arm concept and actually cutting wood with a radial-arm saw. What may have been a highly-anticipated purchase can result in complete and utter disappointment. Most especially, if the machine was a brand other than DeWalt.

With a couple uneducated moves, the thrill can disappear very quickly! And it can be replaced with pure fear.

Attesting to that, one of my sons recently purchased a mint-condition DeWalt, 40 years old or more. The owner had made one cut with it and something happened. Whatever it was, he put the machine back in the box and never opened it again. We bought it from his widow (he had died a natural death!) for a ridiculous price. The only thing wrong with it was the operator. He had purchased it from a source who knew even less about it than he did.

He had bought a box full of ignorance.

Most of the trouble stems from this — Table-Saw vs. Radial-Arm Saw.

Almost anybody can operate a table-saw because he understands one thing: HE will have to PUSH the board for every cut he makes.

This also means that he is completely responsible for the results he gets. If his cross-cuts are a little off-square or his miters have a little gap between them, he has no one to blame but himself! The machine, of course, could have done it perfectly—if only he were more professional.

And he accepts that as a fact.

Not so with a radial-saw. That machine is always assumed to be at fault—never the operator. Oddly enough, this is not far from the truth. But the real truth is that the operator knows too little about his machine. And, over the past 30 years (specifically, since B&D bought it), there were too few places for him to go for knowledgeable help.

Long gone are the days when machine and tool manufacturers vied for position and acceptance in front of the public—in an actual win-or-lose struggle. Virtually gone is the dealer who can professionally demonstrate a radial-saw (even a table saw!), professionally align it, and guide the customer toward the satisfaction for which he is paying. Equally unfortunate is the fact that over 20 different makes of radial-saws have come and gone (or should go!)—each one sucking up little or large portions of the market—and few of them deserving of a crumb.

The abilities of a DeWalt (and I speak only of DeWalts throughout this book) are almost unbelievable.

As a saw (80% of your woodworking), as a dadoing-machine (10% of your woodworking), and as a shaper (3%)—older DeWalts are absolutely unbeatable.

However, the same DeWalt—in misalignment, or with the wrong blade, or in the wrong hands—can not only be frustrating —it can maim the operator for life.

And that just may be YOU.

I do not mince these words: Stupid, uneducated mistakes can maim you for life! (That’s a long time.)

This is just as true for a table-saw—but, remember, the machine is never wrong! It’s your fault when you can no longer count to ten on your fingers.

There are few (if any) sources for learning to “master” a DeWalt. I know of absolutely none.

The next best thing is a book like this.

So let’s get going... now we get to the good stuff!